Hard Data

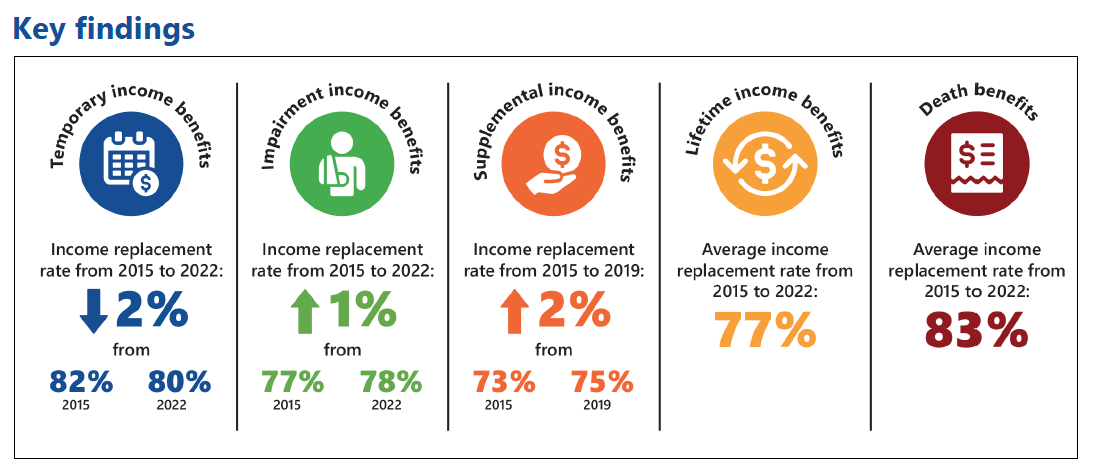

In 2005 the Texas Legislature created the Texas Workers’ Compensation Research and Evaluation Group (TWCREG) to “collect data and conduct research to evaluate the effectiveness of the workers’ compensation system.” See Texas Labor Code §405.002. Since then, the TWCREG has put out regular reports that are accessible by the public which contains data about the Texas Workers’ Compensation System. This month, the TWCREG published a new report, “Income Benefits in the Texas Workers’ Compensation System” The report sets out its “Key findings” in the chart below.

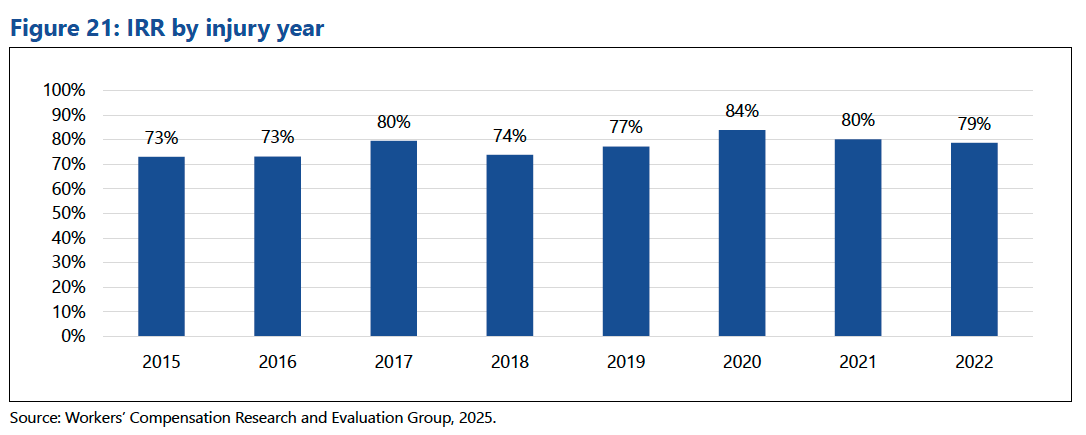

One has to wonder what kind of agenda is being pushed when the report claims that “[a]verage income replacement rate” for Lifetime income benefits increased by 77% and Death benefits by 83% when the data in the report showed no such thing. For instance, Figure 21 on page 25 shows that for Lifetime income benefits, the average income replacement rate fluctuated between 73% in 2015 and 79% in 2022—hardly a 77% increase!

The same fuzzy math is demonstrated in Figure 22 on page 26 where it shows the average income replacement rate for death benefits fluctuated between 83% in 2015 and 86% in 2022.

But this isn’t the only thing misleading about the report. When looking at the data in the context of the last 25 years, it paints a stark picture of the benefits being paid to Texas’s workers.

Looking Deeper Into the Data

As stated, Texas has been keeping publicly available records on the data within the workers’ compensation for a long time. And periodically, they publish reports on that data in order to report to the Texas Legislature what is going on within the Texas Workers’ Compensation system. In 2018 they produced a Powerpoint titled, “An overview of key trends in the Texas workers’ compensation system–2018.”

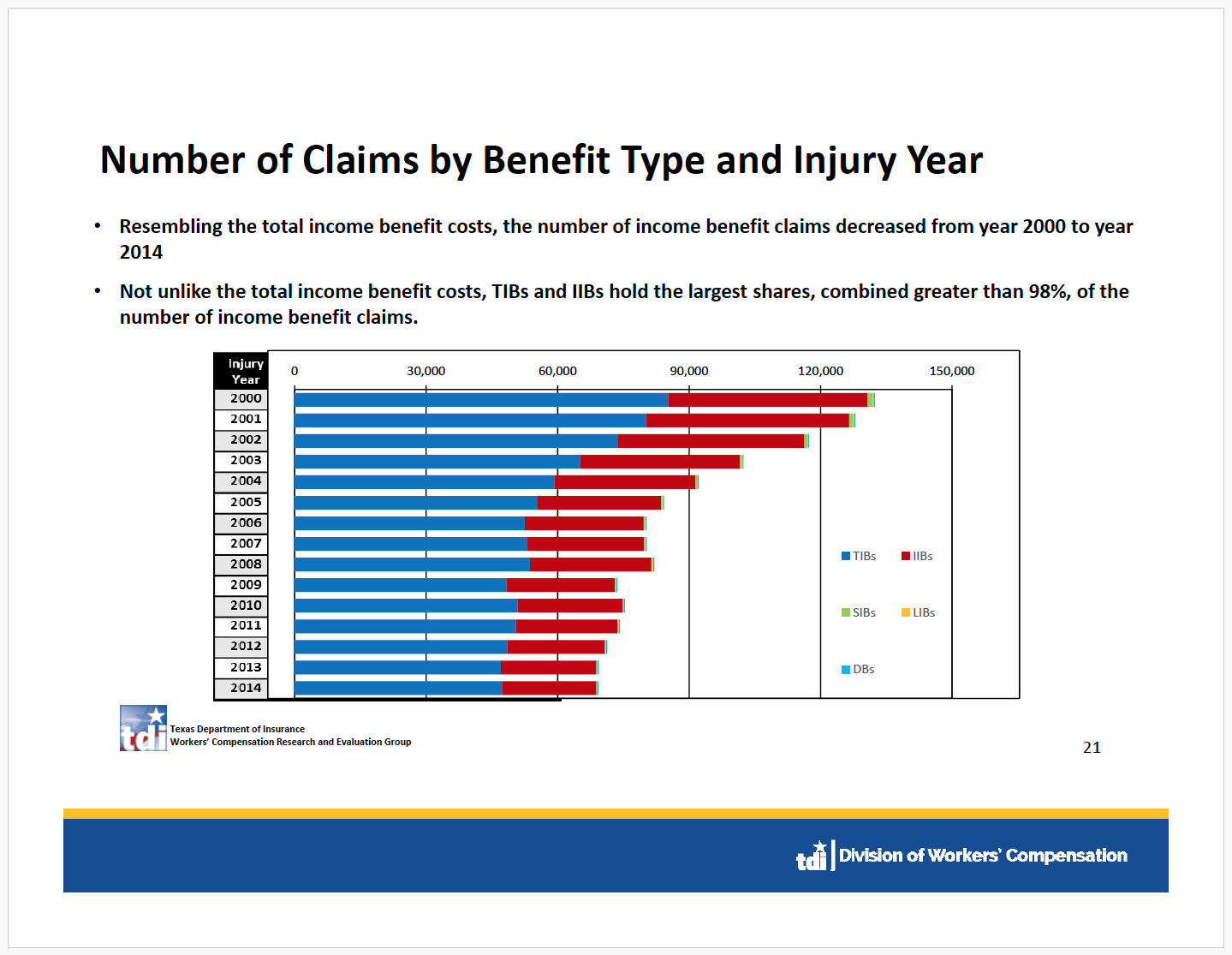

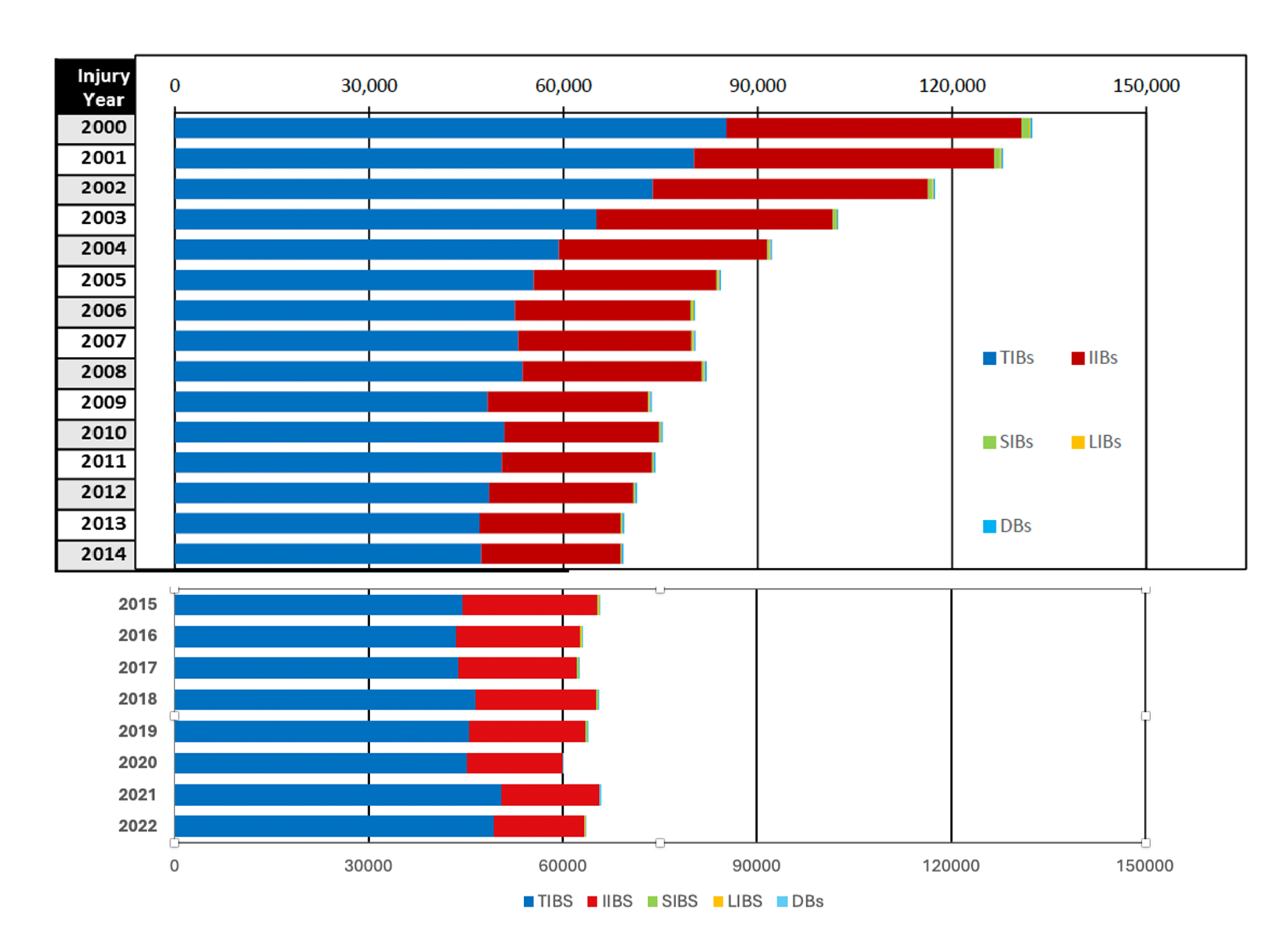

Looking into the data within that report and comparing it to this July’s report gives us some interesting data. For instance, look at the number of claims filed by benefit type and by year. The 2018 report showed the number of claims have decreased since 2000.

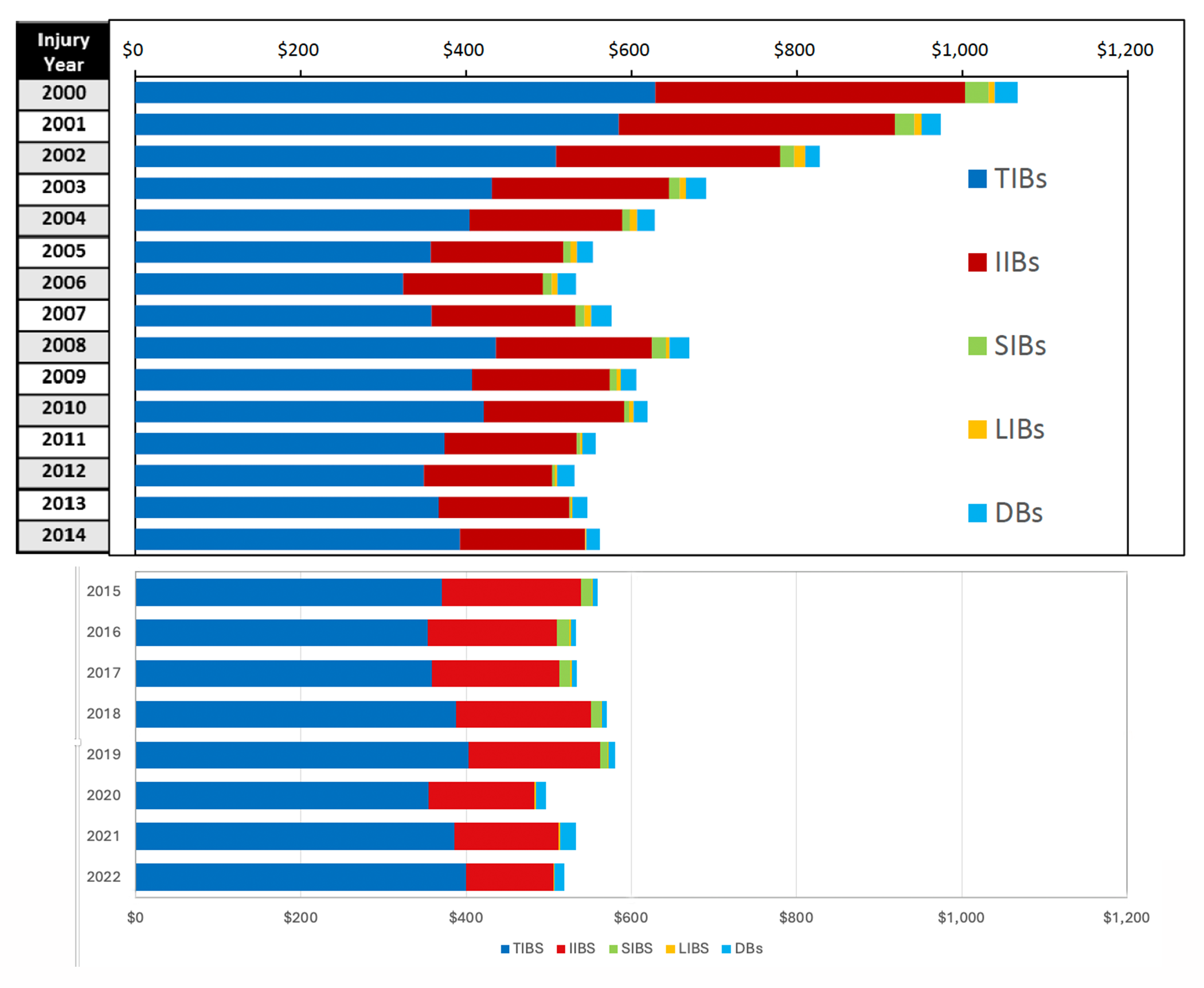

It also shows the amount of money in millions of dollars that Texas workers compensation insurers were paying out in claims each year based upon benefit type. Important to note about this is we are only dealing here with the money being paid to injured workers. This does not include health care costs of which the injured worker gets no economic recovery.

Now let’s compare the data in the slides above with the data published this July.

First off, when we compare the number of claims filed in the 2018 slide with the data from the July report (page 10, Table 2), what we see there was an initial decrease between 2000 and 2008 followed by a leveling off of TIBS claims with a decrease in claims for other kinds of income benefits, particularly IIBS.

While the decrease in claims filed was dramatic at first, the decrease in numbers slowed but has still continued to trend downwards. The key is, though, that the number of Texans in the workforce has not remained static. According to data published by the federal Bureau of Labor Statistics, the number of Texans in the workforce increased by a whopping 42.7% between 2000 and 2022. So the share of workers filing claims as a percentage of workers in the workforce has had a dramatic decrease, from 1.2% in 2000 to just .43% in 2022!

But that’s not all. Let’s look at the actual figures being paid to injured workers. After all, in the last 25 years we have seen huge improvements in industrial safety, even if much of it has come from machination and automation of industrial production. When we take the data in the July report and we include it in the 2018 chart what we see is that claim expenditures have largely stabilized between $400 million and $600 million dollars a year.

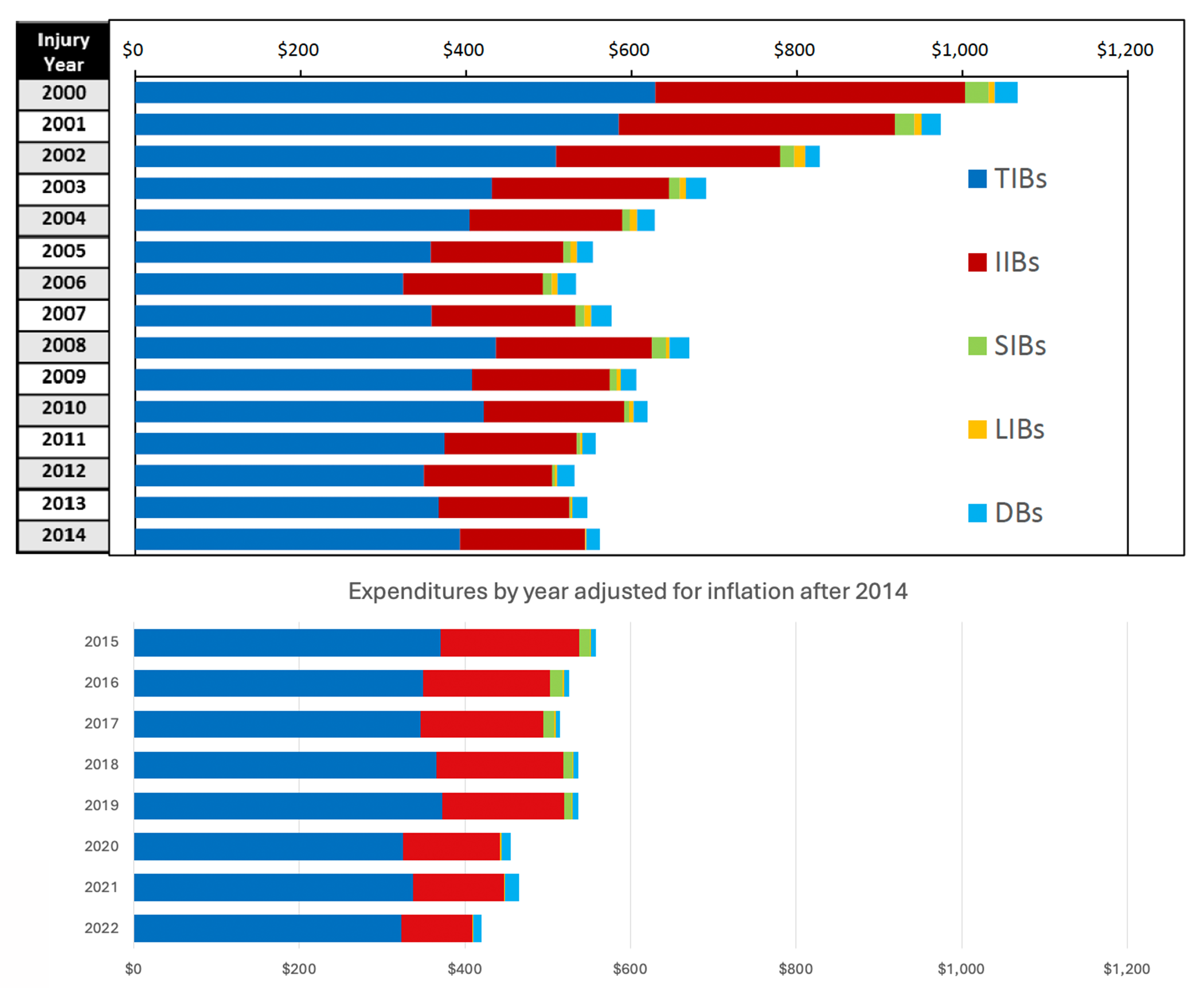

The problem with this data, though, is that it fails to account for the purchasng power of the dollar relative to previous years. For instance, when we adjust the values published in the July report based upon the consumer price index in 2014 we see that the workers compensation costs are continuing to decrease since 2014.

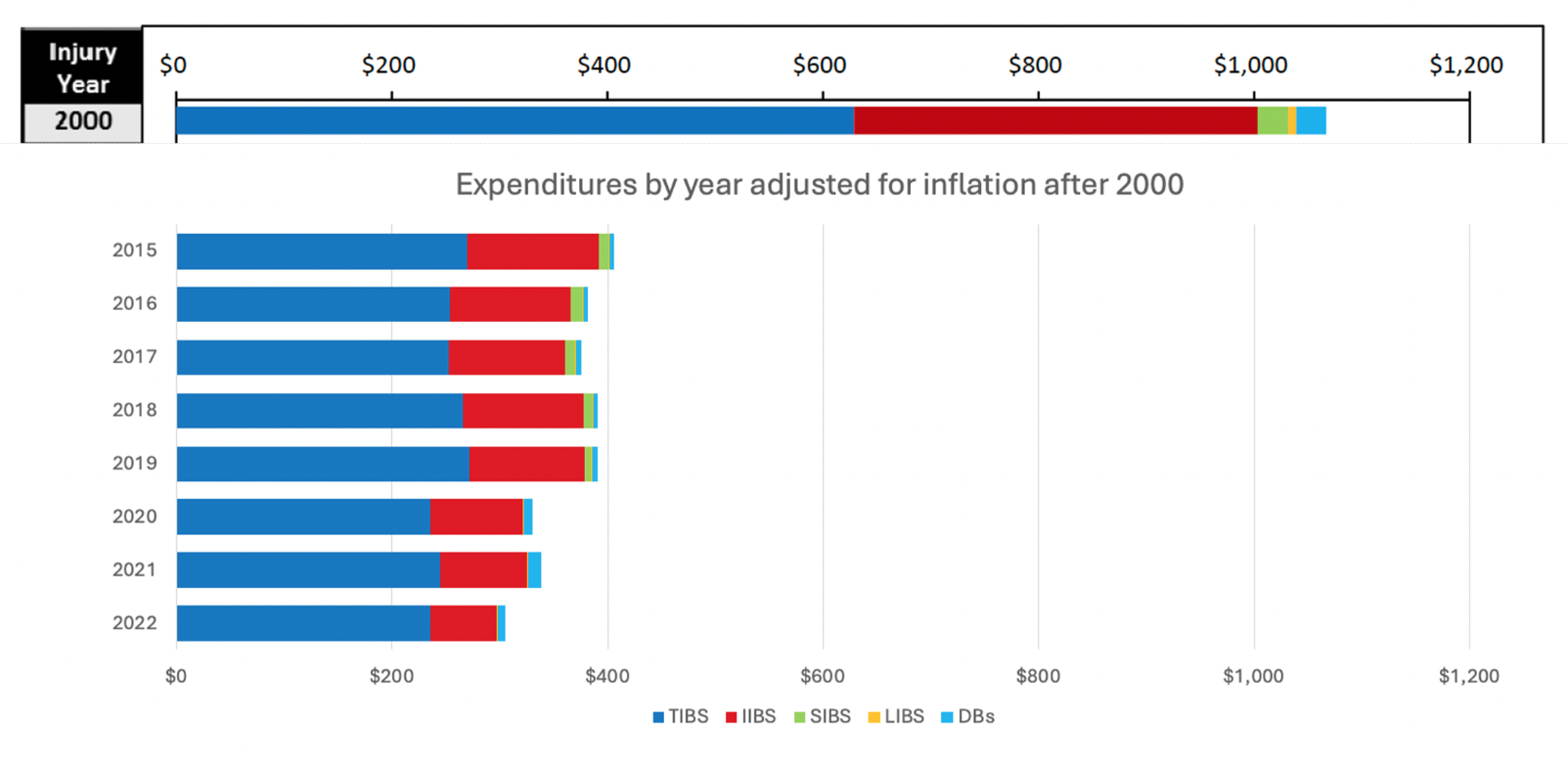

Now the trendline is evident with real costs showing a decrease from close to $600 million dollars in 2015 to an amount that is closer to to $400 million in 2014 dollars. But the thing is, the data from the 2018 slides is not adjusted for inflation, either. Thus, when we compare the July data with the inflation data since 2020, a more perverse picture emerges.

The economic cost to the Texas economy of income benefits paid to injured Texas workers in 2022 is a third what it was in 2000! Keeping in mind that the Texas workers’ compensation system was overhauled due to costs during Governor Ann Richards’ tenure, one can see that Texas workers rarely take income benefits under Texas’ workers compensation system and when they do, those benefits are a shell of what they once were only 20 years ago.